Rail to rescue us from climate emergency

Our history is rich in irony and the climate emergency provides a perfect example.

The 200th anniversary of the Stockton and Darlington Railway is just six years away. The technology that once burned carbon to carry more carbon from pit to port began a transport revolution that transformed the world in the 19th century.

Yet in its modern form, rail technology is called upon to help save the world in the 21st.

Lovers of historical irony will also observe that Greta Thunberg, who graced the cover of Railwatch 160, shares a common trait with locomotive pioneer Richard Trevithick in that both refused to go to school.

At Railfuture’s recent AGM we put Climate Emergency at the heart of our campaigning, secure in the belief that the railway is an indispensable component of any low carbon transport policy.

In Railwatch 160 Ian Brown expands on this theme but raises two areas of concern. First that our arguments need to be rational and evidence-based, and second that the railway is at risk of being caught up, or even overtaken, by research investment in decarbonising road and even air transport.

In familiarising ourselves with supportive arguments I recommend Sustainable energy without the hot air by the late David McKay, who was a member of Railfuture.

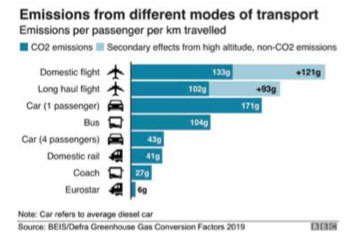

His book is available as a copyright-free download. As its title suggests, it is primarily concerned with energy policy, but since transport consumes about one third of all energy requirements and about a quarter of our carbon emissions, understanding the relative efficiencies of transport modes will be the key to closing the energy gap as well as striving for carbon neutrality.

The book contains many enlightening tables, including one which shows the energy consumption of different modes in kiloWatt hours.

The poor energy performance of hydrogen vehicles results from the amount of energy required to make the hydrogen in the first place.

While research budgets are devoted to demonstrating hydrogen trains, we have to ask how much we are prepared to pay to be green and how many seats we are prepared to give up to make room for storing this fuel. Aviation requires about 40kWh per 100 ton km just to stay off the ground and, because of the distances travelled, needs fuel with a high energy density.

The technology to electrify our railways, however, has been around for over a hundred years. Our problem is not how to do it. We have just forgotten how to do it cheaply.

Freight

A similar table deals with freight and shows that rail is 10 times more energy efficient than road and 16 times more efficient than air. So if we are to consume less energy we need to choose our mode with care.

Carbon

Switching to low carbon transport is a complex process but it is pretty clear that a combination of electrification and energy efficiency is the way to go. So what are the possibilities?

Electric cars are well on the way. Current models have a range of up to 200 miles, plenty for most people to get to work and back or to their nearest rail station.

Their demand on the national grid can be surprisingly low because they can be charged overnight and smart charging (vehicle to grid) allows the unused power to be fed into the network in the evening peak and recharged again in the early hours. About 7kW per vehicle per day should be enough.

Buses are more of a challenge. Tram systems are initially expensive but surely must be rolled out in more towns and cities in future. Rural bus transport is more difficult.

Rail transport is the clear winner for both passenger and freight but more electrification will be needed and an increase in generating capacity, either renewables or nuclear, inevitable.

Road freight is probably the most difficult to convert to electricity because of the amount of batteries required. Lorries burn at best 62 grams of carbon per ton kilometre.

Rail by comparison on average burns about 15 grams and, if electrified, almost nothing.

Local distribution can be by electric van.

Shipping burns about 10 grams and is surprisingly efficient because of the size of vessels now in use. Those calling at our major ports are large enough to fit an aircraft carrier inside them. It is difficult to see a low-carbon alternative for international freight, although nuclear ships could be the way forward.

Of all forms of transport aviation is the most difficult, being dependent on internal combustion.

Tax

How are the various modes of transport taxed? Most have a fixed element (ownership) as well as a distance travelled element (distance moved). Arguments between modes tend to focus on one element and ignore the other, depending on who is arguing the case.

Car drivers pay 20% fuel tax but the rate has been frozen for years and electric car drivers pay only 5% VAT.

Bus companies can claim VAT back and can claim a not-very- generous bus services operator’s grant. Lorry companies can claim VAT back and of course fuel duty is frozen for them too.

Aviation

Aviation is the most polluting form of transport available to the public. It is often argued that taxing aviation is a non- starter as it would require international agreement, but is this sustainable?

Do we really believe that with European Union-wide agreement, airlines would fly to (say) Zurich rather than Frankfurt? Would people stop flying to America given the option of a tax-free return flight?

There are those who argue that taxing aviation amounts to a “sin tax”. But if we believe that the “polluter pays” for other forms of environmental damage, then why not aviation?

We tax alcohol, road fuel, tobacco and more recently sugar, not just to raise revenue but to change behaviour. The landfill tax is a successful example.

Growth in air travel has levelled off over recent years while rail grows to bursting point. We need transport taxes to fund the supporting infrastructure.

Should we continue to expand airports (“sinfrastructure”) at a time of rising environmental awareness or invest in less polluting schemes?

How much would it raise?

Research in this area is not straightforward as much depends on assumptions about changes in behaviour by airlines as well as passengers, and the calculations required start from estimates. But we might raise £11 billion of tax revenue a year.

HS2 will probably cost £50 billion, the East West Rail central section £3 billion, Northern Powerhouse rail £21 billion, Crossrail 2 £32 billion. Completing 200 kilometres of electrification each year at £1 million per single track kilometre would add up to £0.2 billion a year.

The issue of aviation tax is rising up the international political agenda. What should be Railfuture’s response?